TEXTILES

U.S. Textile and Apparel Industry Inching Forward After Steep Asian Competition

The U.S. textile and apparel industries have seen revenues slowly rise over the last seven years as free-trade agreements and rising Asian prices have given local textile and clothing makers a bit of a reprieve.

In 2016, production of U.S. man-made fiber and filament, textiles, and apparel shipments totaled nearly $75 billion, an 11 percent increase from 2009, according to the National Council of Textile Organizations, which recently released its “2017 State of the Industry Address.”

That slight annual increase in production is good news after the apparel and textile industries were walloped with major overseas competition in the 1990s and early 2000s.

“It has been a fairly stable and strong environment for about five or six years,” said Auggie Tantillo, president and chief executive of NCTO, a Washington, D.C., trade group that represents about 85 percent of the textile companies in the United States. “But the market has been flat for 18 months due to sluggishness in the global and U.S. economies and the uncertainty in the retail sector.”

Yarns and fabrics accounted for $30.3 billion, or nearly half the shipments sent out, while carpet, home furnishings fabrics and other non-apparel sewn products made up $24 billion in revenues. Apparel came in at $12.7 billion.

One of the U.S. textile industry’s saviors has been free-trade agreements that require that regional yarns and fabric be used in production. If you look at the $13 billion man-made fiber, yarn and fabrics exported from the United States, a big chunk, $4.4 billion, is sent to Mexico, $1.6 billion is shipped to Canada, and another $1.3 billion is earmarked for Honduras. The Dominican Republic receives $759 million in shipments. All these countries are members of either the North American Free Trade Agreement or the Dominican Republic Central America Free Trade Agreement.

Tantillo said the U.S. textile industry exports about 40 percent of its production and more than half goes to Mexico, Canada and Central America.

Still, there are ways to increase U.S. textiles exports to free-trade partners. And President Donald Trump could have a big role in that.

NAFTA—the free-trade agreement between the United States, Canada and Mexico—went into effect in 1994 but still has trade-preference levels written into it. Trade-preference levels allow a certain amount of yarns and fabric produced outside the free-trade-agreement region to be used in apparel production as long as the non-regional goods are cut and sewn within the free-trade countries.

Currently, Mexico is allowed to bring in 45 million square-meter equivalents of yarn and fabric a year from places such as China, which it normally uses up halfway through the year. Canada has an annual allotment of 88 million square-meter equivalent units, although it most recently used only about 25 million of that. “That is a degradation of the yarn-forward requirement [for the free-trade pacts], and we think that is a problem,” Tantillo said.

When Trump discusses changes to NAFTA, the U.S. textile industry would like to see these trade-preference levels eliminated. Doing away with these loopholes would undoubtedly boost U.S. textile exports, textile producers said.

When NAFTA was being negotiated more than 25 years ago, Canada asked for a TPL because it did not have a strong textile industry.

Still, the U.S. textile industry believes NAFTA is a pillar upon which the U.S. textile supply chain has been able to grow. Canada and Mexico are the biggest U.S. textile markets. Also, Mexico has a lot of apparel factories sewing clothing for retailers and manufacturers who need a quick turnaround on goods.

Domestic push

The U.S. textile industry would like to see several steps taken to encourage more domestic production. It also fully supports the Trump administration’s call to negotiate more bilateral free-trade agreements that would have yarn-forward regulations encouraging the use of American fibers, yarns and fabrics. However, the trade group is opposed to a free-trade agreement with Vietnam, now the No. 2 maker of clothing imported into the United States.

Vietnam, which is turning into a cheap alternative to China, is a Communist-run country that has a non-market economy, NCTO maintains, and would heavily disrupt the U.S. textile industry if goods were allowed to enter the country duty-free.

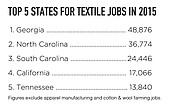

The U.S. textile industry is hoping to add to the 565,000 people employed in the industry last year—with 131,300 working in apparel manufacturing and another 113,900 employed in yarns and fabrics.

The U.S. textile industry is recovering from some hard times experienced in the late 1990s through the early part of the 21st century, when business was dropping 10 percent each year. “There was a confluence of events starting in late 1999, when the Asian currency crisis occurred and practically every Asian currency collapsed by 30 to 40 percent, causing exports to surge to the United States. Then you had China joining the World Trade Organization in 2001,” Tantillo recalled.

But things are turning around. Investments in U.S. textile fiber, yarn, fabric and other non-apparel textile production grew to $1.7 billion in 2015, a 75 percent rise from the $960 million invested in 2009. “I would say the feeling is upbeat, and there is a positive outlook for the industry,” Tantillo said. “There is a level of frustration with the slow economy and sluggishness in the market, but we all know markets are cyclical.”