TEXTILES

Cotton Prices Holding Stable as China Continues to Sell Off Its Reserves

Cotton prices should remain on a level playing field and even decline a bit next year as farmers around the world plant more acreage.

The 2016/2017 cotton season was a banner year for U.S. cotton exports, which were up 50 percent over the previous year as a changing monetary policy in India late last year put a temporary dent in that top-producing cotton country’s ability to export more of its product.

“Deeper into the cotton season, India, the No. 2 exporter of cotton, had some macroeconomic reforms announced in November,” said Jon Devine, senior economist of Cotton Inc., the research and marketing company in North Carolina that represents upland cotton producers and cotton importers. “The reforms were ahead of cotton harvest time in India and threw a monkey wrench into the international cotton market. India was not there to compete with U.S. cotton.”

Because of that, the United States, the largest cotton exporter in the world, sold 14.5 million bales this year compared to 9.2 million bales the previous year after farmers planted 15 percent more acreage as corn and soy prices dipped, Devine said. The U.S. exports 95 percent of its harvest—in the form of fiber and yarn—primarily to Asia and Latin America.

U.S. cotton production should increase again next year because farmers are boosting their cotton acreage, said Leslie Meyer, an agricultural economist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture. “The latest estimate from the USDA is that the U.S. crop will be at about 19 million bales for the 2017/2018 year [which begins Aug. 1]. That’s an 11 percent increase over the previous year.”

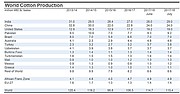

India, the world’s largest cotton producer, and China, the second largest cotton producer, will be reserving more land for cotton growth. The USDA estimates that next year, global cotton production will shoot up 9 percent.

Meanwhile, the global demand for cotton next year is expected to inch up 3 percent over this year as yarn-spinning mills in Bangladesh and Vietnam up their production and China continues on a steady course as the world’s largest textile manufacturer, the USDA reports. In the last four years, global demand has grown between 1 percent and 1.5 percent a year.

With supply outpacing demand, cotton prices are expected to remain at around the 70-cents-a-pound mark in the near future and perhaps fall later in the year. Last year, cotton went as high as 82 cents a pound. “In the last couple of years, prices have remained softer,” said Karin Malmstrom, director, Cotton Council International, for China and Northeast Asia, who recently gave a webinar on the cotton supply-chain situation. “Since last year, the prices have remained firm, which is not a bad thing. In the last few years, the cotton market had a huge roller coaster, which makes it hard to plan and make commitments.”

China’s cotton storehouse

China, the world’s largest cotton consumer and the second-largest cotton producer, has gradually been selling off its huge stock of cotton it started warehousing in 2011 to support its farmers with premium prices. At that time, world cotton prices eventually hit $2.27 a pound, the highest it had been since the U.S. Civil War.

But cotton can’t be hoarded forever because it starts to deteriorate after a few years. So in late 2013, China started selling off its vast reserves, which peaked at 68 million bales and is now down to about 40 million bales, but that is still about twice the annual production seen in the United States. “We see this as a stabilizing factor,” Malmstrom said. “In the past, we’ve had two different balance sheets—one for China and one for the rest of the world. In the next couple of years, we may be working off of one balance sheet.”

Chinese textile factories have been buying up this older cotton and mixing it with new cotton to improve the cotton reserves’ quality, said Meyer of the USDA.

Even with millions of cotton bales sitting in warehouses, China is expected to up its cotton harvest next year—primarily in the western Chinese province of Xinjiang—by 5 percent to 8 percent.

With China supplying most of its own cotton in the last few years, the two biggest export markets for U.S. cotton have been Bangladesh and Vietnam as those countries increase yarn production.

“About 80 percent of the spinning capacity in Vietnam has Chinese investment or is Chinese-owned,” Malmstrom said. “The large companies in Vietnam spin that cotton into yarn and export it back to China.”

Chinese investors entered the Vietnamese market because they expected Vietnam would become a member of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a free-trade pact between the United States and 11 other Pacific Rim countries. That would have made it possible to export yarn and even fabric from Vietnam to the United States free of duty.

But even though the United States dropped out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, China is still strong in Vietnam because China is the largest textile producer in the world and will continue to be for some time.