FINANCE

UCLA’s Anderson Forecast Delivers Good News

Nothing’s more welcomed these days than surprise good news. And that’s what came in the latest UCLA Anderson Forecast—the prominent economic report put out by the University of California Los Angeles’ Anderson School of Management—which is cheerfully titled, “The Unexpected Robust Economy.”

Recessions follow boom times, but according to the same law that ensures autumn follows summer, the good news is that while 2024 will see a slowing in the national and state economy, no immediate recession is on the horizon.

The California Apparel News listened in on a recent Anderson School symposium and afterward spoke to Jerry Nickelsburg, economics professor and faculty director of the Anderson Forecast, to have him help break down the key takeaways on the current state of the Golden State.

CAN: What should businesses most know about the present economic climate?

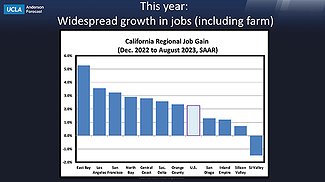

JN: The most important takeaway from an analysis of all the data and what we know about the impact of economic policy, which is the increase of interest rates, is that we are not in a recession, and there’s no indication that we’re about to start into one. I think the underlying message about the outlook in California is that the things that are going to hold up the best in the coming two years are things that are disproportionate in California. And those are going to be technology, the construction industry, and leisure and hospitality. So we’re expecting to see here less impact of any weakness in the U.S. economy and for California to continue to grow faster than the U.S., as it has for some time.

CAN: For a long time California has boasted one of the largest economies in the world. Why is that?

JN: There are a number of elements, starting with the fact that California tends to be an entrepreneurial state where people come to start businesses. There is also a large secondary education system, so there’s a deep workforce and a lot of innovation and experimentation that goes on here.

CAN: What trends are you seeing for the nondurable goods manufacturing sector, which includes the apparel industry?

JN: This sector is much more oriented toward lower-skilled manufacturing, much of which left the U.S. a long time ago. That which remains serves specific purposes, such as the garment industry in Los Angeles.

CAN: In the retail sector, your findings show that people want to be out and spending money.

JN: Retail is interesting because for a long time brick-and-mortar was dead in the water because of the shift to online shopping. But one of the things that came to the fore during our pandemic lockdown was that we wanted to be out with people. So retail, which is not just commoditized but also a little bit more experiential, is doing well, and we’re even seeing investment in more retail establishments.

CAN: The symposium said we’ve entered the stage of a post-industrial society. How do people begin to understand what that means?

JN: A post-industrial society runs on information. Automation, robotics, artificial intelligence—these are things that are transforming goods and services. We’re actually making more goods than before, but we’re doing it in a very different way. So Rosie the Riveter doesn’t exist anymore, but Rosie the Robotics Technician does. As for something like sustainability, what we’re seeing nationally through the Inflation Reduction Act, and in California, are policies that encourage the use of alternative energy, and that has created a demand for innovation and production of new equipment and new ways of doing things that weren’t there before.

CAN: The symposium also had an interesting section that may be confusing for the layperson, and that is the relation between recession, inflation and unemployment. Can you explain their connectedness?

JN: If one looks back at history, one finds that dramatic drops in inflation rates have been associated with recessions. The reason is that recession is caused by a decline in demand for goods and services, and when demand is in decline businesses will typically lower their prices, and that’s what brings high inflation down to lower. What we’ve seen recently is that high inflation was related to supply-chain interruption, and as that has gone away we’ve had a decline in inflation without having a recession that, for example, in 1981 brought down very high inflation rates. Unemployment gets triggered when there is slack demand for a firm’s production—it doesn’t hire and many times lays off people. So the three things are really all kind of simultaneous.

CAN: However, you say that while recession is inevitable, because of the cyclical nature of the economy, we’re not immediately headed into one.

JN: Based on history, you can expect one at least sometime between now and 2034. The point of saying a recession is inevitable is because economies build up imbalances over time, of which there aren’t any right now, and recessions are a correction of imbalances. So that’s bound to happen sometime, and saying it’s inevitable is an attempt at humor regarding all those who say it’s coming next quarter.

CAN: Closing on a somewhat lighter note, how do you personally modify your behavior in the wake of all the information you have at your fingertips?

JN: I think it’s important for everyone to look at data, and look behind rhetoric, and then make the best decisions that they can based on the best available data.