How Missteps in Trade Could Flip the U.S. Economy

Trade and tariffs could be the make or break factors when it comes to growth of the U.S. economy.

Experts at the UCLA Anderson Forecast, who released their second-quarter economic report for the country on June 13, were upbeat about the future but noted that President Trump was playing with fire when it came to restrictive trade measures and tariffs.

“We can sleepwalk into a serious economic accident,” wrote David Shulman, a senior economist with the UCLA Anderson Forecast.

The dust up over tariffs took center stage following the recent meeting of the G-7 in Canada, where President Trump wouldn’t back down on his aluminum and steel tariffs against long-time allies including Canada and Mexico. The G-7 comprises U.S. allies France, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, Japan and Canada.

The aluminum and steel tariffs prompted Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to stand before a phalanx of TV cameras and announce that his country's citizens are polite but won’t be pushed around by the Trump Administration. Trudeau then threatened tariffs on U.S. products exported to Canada, one of our largest export trading partners.

In 2017, the U.S. exported $341.2 billion in goods to Canada and imported $332.8 billion in goods from Canada, giving the U.S. an $8.4 billion surplus. A trade war is bad for business, as seen as in the fluctuating stock market reacting to the uncertain trade future. “This is not good,” Shulman said. “If it is broad based enough, you can make a recession.”

On top of tariffs, the United States still hasn’t wrapped up negotiations with Mexico and Canada over an updated North American Free Trade Agreement. UCLA economists fear the left-leaning candidate Andrés Manuel López Obrador will win the presidential election in Mexico this July, which would threaten a renewed agreement.

“A trade war implies higher tariffs and non-tariff barriers that work as a tax on the American people that would raise prices and restrict output,” Shulman wrote. “This is hardly the recipe for economic growth.”

Still, without major disruption, the economy will continue to expand at a measured pace through 2020. Gross domestic product is expected to rise 3 percent for the balance of this year when measured from the fourth quarter of 2017, but then it will take on a more moderate pace with GDP growing 2 percent in 2019 and 1 percent in 2020.

The slowdown will be because the country is nearing full employment and the economy does not grow as quickly if there is not a rise in productivity. “The current strong job growth, which averaged 200,000 jobs per month in 2017 [in the United States], is not sustainable in a full-employment economy,” the UCLA Anderson economists wrote in their report.

They predicted that job growth would average 133,000 a month for the rest of 2018 and then decline to 85,000 per month in 2019 and 60,000 a month in 2020. The current U.S. unemployment rate of 3.8 percent is expected to dip to 3.4 percent by mid-2019 and then move back up to 3.8 percent by the end of 2020.

For several years, California has been adding more jobs as a percentage of the workforce than the rest of the country, but being the most populous state with 39.5 million residents, the state’s unemployment rate is a bit higher at 4.3 percent. It should hold steady at 4.3 percent by 2020.

One interesting fact about California is the state continues to shed more manufacturing jobs in areas including durable goods and apparel but is bulking up on technology jobs in Silicon Valley in Northern California and Silicon Beach in seaside communities around Los Angeles.

The UCLA Anderson Forecast predicts that total employment growth in California will be 1.7 percent in 2018, 1.8 percent in 2019 and 0.8 percent in 2020.

While unemployment rates will remain lower, interest rates will go higher. The Federal Reserve raised the benchmark interest rate by a quarter of a percentage point on June 13 to between 1.75 percent to 2 percent “The consensus is there will be two more raises in interest rates this year—one in September and one in December,” Shulman said.

The rise in interest rates is being propelled by higher inflation, higher wages and an exploding federal deficit, Shulman wrote in the forecast. Inflation on a year-over-year basis measured by the consumer price index already exceeds 2 percent and should go up to 3 percent by 2020. Wage increases, which recently rose by 2.5 percent over last year, could rise by 4 percent year-over-year in 2020.

Higher interest rates will have a major effect on housing construction because borrowing by real estate developers will become more expensive and cut into project developments.

Housing starts across the country remain well below their long-term average and are a far cry from earlier boom periods. U.S. housing starts will increase in 2019 to 1.4 million units but decline to 1.36 million units in 2020. That is below the 59-year annual average of 1.435 million units between 1959 and 2017.

The UCLA economists wrote that housing starts have been the greatest disappointment of the economic recovery and expansion, which began in 2009. This lack of housing will only exacerbate the growing affordability problem in the urban areas of California. And that will continue, with housing prices expected to continue their upward march.

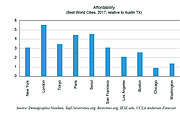

Part of this is due to the fact that California’s coastal cities remain desirable places to live for local residents and wealthy foreigners looking for a second home in which to invest. Since 2000, housing prices across the country have risen 97 percent, but in Los Angeles they were up 178 percent above 2000 prices. Chicago and Atlanta housing prices have grown only 42 percent in the last 18 years.

“Robust job creation [in California] has been and will continue to put pressure on housing demand,” wrote economist Jerry Nickelsburg.