UCLA Economists Predict a Healthy 2018 With Clouds on the Horizon

The economic world has been pretty rosy in the last few years with consistent growth, falling unemployment rates and rising wages.

That picture of health will continue through 2018, but UCLA economists are seeing some headwinds approaching in 2019.

“There is a momentum coming from the recent strength in 2017, strong equipment spending, the likelihood of a tax cut and a consumer that is benefiting from higher-asset prices and the prospect of higher wages,” said UCLA senior economist David Shulman, one of the economists who wrote the recent “UCLA Anderson Forecast for the Nation and the Economy,” which was released Dec. 6.

One of the more recent movers and shakers to the economy includes a giant jump in equipment purchases, up 8 percent in the two most recent quarters. That is expected to continue into next year and help push the country’s gross domestic product to a 3 percent expansion through the second quarter.

However, by the middle of next year, GDP growth will probably slow to 2 percent, which has been the standard annual rate of growth for the last couple of years.

Another positive force on the economy will be the government’s rising defense budget as the administration gets more aggressive in dealing with North Korea, situations in the Middle East, and concerns about Russia and China. Defense spending, which declined over the last seven years, will see a rise of 2 percent next year and 2.7 percent in 2019.

That bodes well for California. “California still has high-value defense spending taking place in California even if many of the companies have left the state,” Shulman said.

The drone industry is one of Southern California’s strong new economic growth areas, and Northrop Grumman recently hired 1,000 people at its aircraft plant in Palmdale to work on the Air Force’s B-21 bomber. By the mid-2030s, the Air Force is expected to purchase 100 of the stealth jet bombers, which can slip behind air-defense systems.

But the cloud on the horizon is the fact that the U.S. unemployment rate is expected to dip to below 4 percent from its current 4.1 percent. With a labor shortage in the offing, employment growth could plateau, reducing GDP growth to 1.5 percent in 2019.

“The economy grows by adding people to increase productivity,” Shulman said. “With full employment, it is harder to add people.”

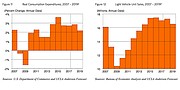

Consumers will continue to keep their wallets open and make purchases. Real-consumer spending will rise next year to an annual rate of 2.8 percent, up from 2.7 percent this year. But with car sales expected to lose speed, consumer spending will inch down to 2.2 percent by 2019.

“However, as long as stock and house prices remain elevated, the consumer, or at least the high-end consumer, will remain in good shape,” Shulman wrote in the report.

Economists were holding out hope for the budget consumer after Walmart reported that its same-store sales for the most recent quarter were up 2.7 percent.

The Federal Reserve is expected to announce another interest-rate hike this December, after two previous hikes this year, showing the Feds’ confidence in the economy. By the end of 2019, benchmark interest rates could be up to 3 percent from the current 1.375 percent. Next year could see three more increases, UCLA economists said.

The California housing problem

Rising interest rates and the new tax-reform law being shaped by Congress could have a huge effect on economic growth in California, according to Jerry Nickelsburg.

Housing is already expensive in the state, but with property-tax deductions being limited to $10,000 a year and state and local taxes no longer being deductible from federal tax returns, many future homeowners will see their disposable income shrink.

“Let’s take the potential homeowner, a millennial software engineer looking for that first house. Prior to the tax change, he or she deducted state taxes from federal taxes, and their disposable income allowed them to pay a mortgage for one of those very nice California bungalow homes in the San Gabriel Valley,” Nickelsburg wrote in the UCLA Anderson Forecast. “When they are not able to deduct their state taxes, adjusted gross income is higher and the federal tax bill is higher. This is the idea of getting rid of the deduction—higher revenue for the feds to pay for tax cuts elsewhere. But our millennial has lower after-tax income and now the bungalow is out of reach.”

This could lead to lower housing prices down the road as more homes sit on the market waiting for eligible buyers. But it is also a deterrent to attracting workers to the state.

“To continue the very rapid growth in employment likely requires domestic or international immigration to the state or both,” Nickelsburg noted. “With Trump’s policies decidedly reducing international immigration, net domestic migration to California would be required.”

In October, California’s unemployment rate stood at 4.9 percent, down from 5.3 percent the previous October. UCLA economists are predicting that with the new proposed tax bill pushing equipment deductions to the first year of purchase, companies will have more money to hire and the state’s unemployment rate will fall to 4.6 percent by the end of 2019.

Free-trade free fall

Despite a healthy outlook for 2018, economists are worried about the North American Free Trade Agreement negotiations going on right now among the United States, Mexico and Canada.

President Trump has threatened to pull out of the free-trade pact if certain concessions or changes are not made. The most recent negotiations in Mexico City did not go well, and observers are concerned that, if the next meeting in Montreal in late January hits a speed bump, Trump will get frustrated and step away from the negotiating table.

“There is a big risk that Trump could pull out of NAFTA, and that could cause a recession in late 2018 or 2019,” Shulman said, noting that Trump pulled out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade pact and the Paris climate agreement this year. “There is $1 trillion in gross trade volume a year between Canada, Mexico and the United States.”

Most affected would be the U.S. auto industry, where parts made in the United States and Mexico cross the border several times to manufacture a car.

Last year, the United States imported $4.5 billion of apparel and textiles from Mexico, making it among the top 10 suppliers to the U.S. market. In turn, the United States sent $5.9 billion in textiles and apparel to Mexico, according to the U.S. Commerce Department.