INDUSTRY VOICES-How to Buy Prints Without Buying a Lawsuit

It is no secret that there are several print suppliers who have made the filing of lawsuits and claiming copyright infringement their business model. As publicly available court records show, just three such California-based print suppliers alone have filed over 225 lawsuits within the Central District of California. Each lawsuit seeks copyright-infringement damages.The claims extend to the mill from which the print was purchased to the manufacturer and the retailer to whom the manufacturer sold garments containing the allegedly infringing prints. The pendulum has swung way too far from the level of common sense to the draconian operation of the copyright laws.

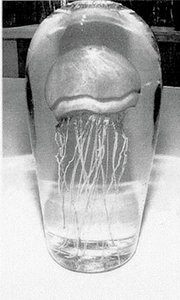

For a work to be copyrighted, it has to be an original work of authorship, according to Title 17 of the United States Code, which concerns copyright. That is, it has to be a creative work developed and conceived out of the artist’s imaginative mind.The real rub comes when the definition of “original” is measured.Generally, the originality standard is set at a very low bar, known in the legal circles as a “modicum of originality.” There are certain things that are not copyrightable, such as images that exist in nature.In Satava v. Lowry, an artist saw a jellyfish display at an aquarium, created glass sculptures meant to look like live jellyfish in a glass case, and obtained copyright registrations for several of his sculptures, including the one shown. That copyright registration was challenged in court. The court found that the design was one that existed in nature and no copyright could be available. But what exists in nature?

Believe it or not, a print commonly known as a “zebra stripe” (pictured) is the subject of a copyright registration. A copyright registration is obtained by filing an application for copyright, identifying the design, requiring the author to sign under penalty of perjury that the work is original and paying a small fee.Not much more is required.The registered owner of the “zebra stripe” in this article will advocate its copyright on the basis that the “zebra stripe” is not an actual design found in nature but rather one that was created by the author.I am not exactly sure how one knows that, in fact, there is no zebra with the same stripes, but nonetheless that is the legal basis by which something as familiar as a “zebra stripe” can be the basis of a copyright-infringement lawsuit. It is the damages that come from lawsuits for infringement that have driven companies armed with a copyright registration to augment their business of selling prints with the business of filing lawsuits.

To get an idea of the scope of damages, there are two levels of consideration:

•Statutory damages If a copyright is registered within three months of the publication (first use by the plaintiff), statutory damages may apply. These damages range from $200 per innocent infringement up to $150,000 for willful infringement.Attorney’s fees are also available to the plaintiff.

•Non-statutory damages Fortunately, statutory damages are not available for registrations which occur after three months from first use. Consider the circumstance in which you purchase a print. You begin to use it and it is not yet registered by anyone, but someone who claims to have a copyright interest in the design— often spurred by possible economic gain—sees the garment, containing what he claims is his print, hanging at Wal-Mart, Target or another retailer’s rack. He then files a copyright application, obtains the copyright registration and then files the suit against you. Although no statutory damages are available in that circumstance, the copyright holder may be able to require you to disgorge all the money that you and your customer made on the sale of garments containing the infringing print. Willful infringement may still expose you to attorney’s fees spent by the plaintiff.

If you have not yet decided to use only non-printed goods in your garments, there are a few things that you might be able to do in order to protect yourself from claims of willful damages, hence making you a much smaller economic target for plaintiffs.

What to do:

1. Confirm with the mill that it owns the copyright. Start with asking the mill if it has a copyright registration of the print it’s offering. If it does have a copyright registration and you rely on that registration, that may be sufficient to sidestep the willful-damages claim.

2. Ask the mill to see evidence of the original-work authorship to review the documents which are the source of the design. In some cases, the mill itself may have bought the design. If so, you may request a bill of sale. Make sure it includes a statement that the seller (the person from whom the mill bought the design) in fact had a copyright registration and is transferring that copyright to the buyer. The mill should also have an assignment of the copyright.

3. Get an indemnity from the mill that covers both you and anyone to whom you sell product. This indemnity can be included in your purchase-order documents. The signature of the mill on that particular order is always recommended.However, the indemnity of the mill may be fleeting. First, the mill may not have sufficient assets to cover the claims for damages. Second, they may be offshore suppliers, where jurisdiction of the federal court may be limited.If the mill is local or offshore, find out if the mill has its own insurance which covers you for alleged copyright-infringement claims.

4. You can buy your own copyright-infringement insurance. Some of these policies can be pricey and hover around $25,000 per year, but it is a small price to pay to protect you and your customer from copyright-infringement lawsuits.

5. Use public-domain designs. There are many designs that are available without issues of copyright ownership. The Fashion Institute of Design & Merchandising and the Fashion Bookstore in the California Market Center both maintain libraries and repositories of thousands of prints that are already in the public domain or that have been determined to exist in nature. We have all seen a Hawaiian shirt with an orchid design on it—that is what makes a Hawaiian shirt to begin with!Many of the orchid designs all tend to blend into one another. In many cases, unless the designs are held side by side, the design differences are sometimes imperceptible. Select a design from one of these repositories, and ask the mill to make it. Of course, you will not have any rights to that design either, but it will certainly keep you out of the courtroom.

6. Conducting due diligence will be strong evidence that you are not a willful infringer, but be careful. It may cut two ways. If you ask for the copyright registration from the mill and it cannot be supplied, and if you asked for original work of authorship and it cannot be supplied, or if the mill purchased the designs and they cannot provide you with a bill of sale and assignment and you still buy the print, which turns out to be infringing on someone’s copyright, you may very well be considered a willful infringer. That is, all the red flags were raised and you chose to ignore them.It is a no-win situation. If you are not comfortable with the response to your due-diligence inquiries, then do not buy the print.

7. Design your own prints. There may be no surefire way to buy and sell printed fabric without the threat of litigation, but that does not that mean you are powerless. There are now things you can do to protect yourself or to substantially limit financial exposure for you and your customer. It just takes a little work.

P.S. On Aug. 27, a federal court issued an order finding that, as a matter of law, the copyright in the zebra-print design is invalid.

Robert Ezra is the senior partner at Ezra Brutzkus Gubner LLP, whose specialties include the garment and textile industries and intellectual-property issues that arise therein. He can be reached at rezra@ebg-law.com. This article is not intended to be comprehensive or a substitute for proper legal advice. Consultation with your counsel is crucial in protecting you from copyright-infringement claims.