Denim: It All Comes Out in the Wash

Shinzo Suzuki’s lithe physique, rolled-up jeans, and sprightly step make you almost think the quiet executive has discovered the fountain of youth. In fact, he’s discovered the cauldron of accelerated aging: In a day or two, Suzuki can take a stiff new pair of denim jeans and make them look like they’ve spent the past 20 years buried under an avalanche.

Suzuki is one of premium denim’s unsung heroes. Like the Wizard of Oz, he directs complex orchestrations of artifice, all while hidden behind an indigo curtain. Formerly the president of Caitac Garment Processing, a Japanese company with facilities in Gardena, Calif. (and the first laundry for Seven For All Mankind), in June, Suzuki founded Vernon, Calif.–based Denim-Tech in partnership with Matsuoka Corp., a $300 million Japanese private-label company. Already providing washing services to denim lines Chip & Pepper and Rogan, Suzuki plans to make Denim-Tech a $50 million company with 1,000 employees turning out 100,000 units per week.

Its specialty? Using custom machinery and hand labor to make blue jeans look completely worn out.

Over the past five years, as the premium denim market has emerged as one of the apparel industry’s most intensely competitive categories, much of the credit has gone to the art of the fit. Salespeople and marketers tout a brand’s slenderizing cut and brilliantly engineered back-pocket construction designed to flatter even the most imperfect derriere.

What gets less credit for a jean’s success depends on the “laundry,” usually accomplished by a subcontractor who specializes in artificially making a jean look vintage.

At Denim-Tech, Suzuki uses stonewashing, sanding, resin, potassium, bleach, pigments, dyes, and oven-baking to replicate the look of a jean naturally aged for 3 to 20 years—and can do this in about 48 hours.

Washing is the most misunderstood aspect of denim processing, says Felix Valdez, a “wet processor” for Old Navy and formerly of Los Angeles laundry The First Finish. Says Valdez, “Does the consumer really stop to think how their distressed jeans got that way?”

The array of washing techniques is so extensive, it makes the need for quality fabric for mid-tier jeans practically obsolete. “I tell [Old Navy parent company] The Gap, let’s not purchase expensive fabrics,” says Valdez, “because in the long run we’re adding so much product to the denim, that at the end of the day it’s not going to matter what it looked like in raw form.”

Designer connection

Washes, rather than fit, drive the denim market, says Kristopher Enuke, owner and designer of Oligo Tissew. Fit has more or less been mastered by premium brands, he says, and the rise of a woman’s jean has become standardized at about six inches. “So the rest of it now is: What’s the hand? What’s the look? Can it command the price you’re tagging on it? And all of that is achieved through the wash.”

Enuke eschews the vagaries of fashion in preference of denim styles that will stand the test of time. His guide is the most iconic jean of them all, the classic Levi’s 501, so Enuke’s primary design goal is to replicate the archetypal look of faded Levi’s. “The closer you are to that, the more authentic-looking and classic, the more longevity you get from the product in terms of wear.”

Oligo Tissew’s most popular jean is called Hidden Dragon. It starts with a stretch indigo jean, and then Enuke sands it, making the inner and outer thigh dark while leaving the middle light. The eye is drawn to the light center of the leg, he says, creating a slimming effect. “From up close, you see just a slight suggestion of it, but from far you see it, and the woman just looks wonderful.” The jean is then over-dyed in black, using resin to provide a sheen that “makes it even more elegant.”

While many washhouses are respected for their techniques, their primary duty is to realize the vision of the designer. “Denim is labor and time intensive,” says Enuke, who tinkers with jeans at night when he’s at home, “and is ruled by passion.” Enuke then works with his laundry to find ways to mass-produce what he has achieved by hand over considerable time.

When it comes to washes, there’s vintage and then there’s, well, antique. Stronghold, according to co-owner Michael Paradise, is one of the five oldest apparel brands in U.S. history and the first denim brand to be made in Los Angeles. Originally founded in 1895, Stronghold has been re-launched as a premium denim line to replicate the look and feel of denim from the early 20th century, says Paradise. The first shipment is for Holiday 2005/2006.

“We’re giving our interpretation of vintage, turn-of-the-century denim, so we shun state-of-the-art washes done for fashion’s sake,” says Paradise. Drawing on archival fabric swatches and antique jeans in private collections, Stronghold will offer selvedge denim in dark indigo washes. And while the jeans will be finished at Los Angeles–based laundries, Paradise guards their identities as top-secret information.

Enuke, who will debut a men’s denim line next spring, knows that whatever techniques he shares with the washhouse will eventually be shared with other clients. “But you hope that your relationship goes deep, and they know that if they put your wash on somebody else’s jeans for the season, that you will start looking for another washhouse.” Though it may become part of the washhouse’s repertoire for a future season, there’s a general agreement that the washhouse will not divulge the designer’s work to other clients. The great unwashed

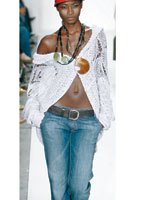

Most denim and trend experts agree that Los Angeles is the world capital of denim, and that is something unlikely to change in the near future, says Suzuki. “Celebrity casual,” Japan’s term for the West Coast look of premium jeans combined with a sexy top or T-shirt and strappy heels is starting to catch on in Japan, adding to the cache of denim that is made or washed in Los Angeles.

But will Los Angeles be able to hold on to its reputation forever? Perhaps not, says one industry insider with decades of experience in the jeans industry, but who wished to remain anonymous, if raw denim becomes the next big trend.

The Japanese and Italians are denim purists, he says, and they like their denim raw, or unwashed. This is the next big trend on the horizon, the insider says, and to the extent that it catches on, L.A. laundries will suffer.

Suzuki points out that raw denim has always been a part of the market. Even if it becomes a trend, it will be confined to a small percentage of the premium market, since most Americans prefer the soft, lived-in feel of washed denim to the cardboard-like fit of a new pair of raw jeans.

And while the anonymous expert agrees that there’s a growing presence of raw denim in retail stores from Urban Outfitters to Old Navy, his prediction is only an educated guess. “Who can predict trends? I’ve been in this industry for years and I can’t know what people are going to buy.”

Global warming

Perhaps the greater threat to Los Angeles’ stature as the global denim capital is the fact that the apparel industry is just that: global. And L.A.’s expert washers may unintentionally harm their cottage industry by training overseas laundries in L.A.’s fashion-forward wash techniques.

Old Navy’s Valdez trains workers at laundries in Bangladesh and China, where factory owners are eager to cash in on the denim craze. “The people who own these facilities have so much money to invest,” says Valdez. They buy the best machinery from Italy, he adds, and hire top consulting firms. “They’ve mastered laser whiskering techniques, which is amazing.” Equally amazing, says Valdez, are development centers, “where you can come and create.” The quality of craftsmanship in China and Bangladesh is also good, he says.

According to Valdez, many brands are outsourcing overseas: G-Star washes in India, Da Nang in Vietnam and Stitch’s in China. “The people there are doing the same thing that laundries in Los Angeles are doing, and probably even better.”

For Valdez, Los Angeles built its reputation more on the hipness of its brands and marketing savvy that ensures the latest size-two ingenue is plastered in magazines in a fledgling brand’s celebrity freebies. “What they [top L.A. brands] know is how to market. But you put them in the laundry [business] and they won’t even know where to begin. They depend on people like us.”

So now that L.A.’s world-class washes can be replicated overseas, Los Angeles will have to work even harder to stay on top, and that means returning to innovation in both design and washing techniques.

That design innovation may already be dawning. “What people are starting to play around with now is non-denim,” says Valdez, “doing denim treatments on twills and T-shirts.”

Even Denim-Tech’s Suzuki, whom Enuke says is poised to become L.A.’s top washhouse, has had to consider taking advantage of the rapid rise in quality of Far East factories for cost-conscious clients. His partner, Matsuoka Corp., has factories from Myanmar to the Philippines. Suzuki plans to take advantage of them by offering clients a wide range of manufacturing and washing options.

Denim brands will be able to choose from every possible combination of domestic manufacturing and foreign washing, or foreign manufacturing and L.A. washing, turning his Vernon facility into more of a product-development center that denim brands can utilize. “So far, response has been very strong,” Enuke says.