Menswear's New Concept: Contemporary

After years of steady sales of contemporary women’s apparel, men are getting in on the action.

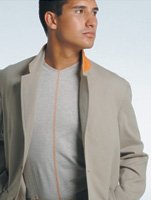

There’s a growing cohort of menswear designers and retailers looking to clothe men in apparel that is fashion-forward, design- driven and unusual. The category has different names, depending on whom you ask. Some call it contemporary menswear, others describe it as young designer, or contemporary streetwear, or even street couture.

The price point is similar to women’s contemporary apparel— and, in some cases, retailers will carry both men’s and women’s, merchandising them side by side or in small “his” and “hers” departments.

Los Angeles women’s apparel designers helped popularize the term “contemporary” several years ago when labels such as Trina Turk, William B., St. Vincent and Alicia Lawhon rolled out fashion-forward apparel for women who were looking for higher quality fabrics and construction than in juniors apparel, but were not ready for missy merchandise.

In recent seasons, designers and retailers are experiencing a similar dynamic as men try to bridge the gap between logo-driven young men’s lines and the conservative suits, sports coats and trousers of more traditional menswear.

“Men are finally starting to realize that they need to put some effort into the way they look,” said designer Darren Gold, who launched his men’s upscale sweats line Gold after he was unable to find track suits with the narrow fit he wanted. Gold is also the co-designer of women’s young designer line Mhope. In addition, he is president of the Coalition of Los Angeles Designers, which includes in its roster of designer menswear lines Andrew Christian, Ryan Roberts and Eisbar.

“[Now] there is more product for men to choose from at different price points and across trends— which has been the biggest obstacle to growth,” he said, explaining that in the past, “with nothing new there was nowhere for the market to go.”

The business of casual

The relaxation of corporate dress codes in the late ’80s and early ’90s introduced men to the idea of “business casual.”

According to Gold, relaxed dressing at work laid the groundwork for contemporary menswear. As men stopped wearing suits to the office, they had to start thinking more about their weekday wardrobe. Eventually the differences between weekday and weekend dressing began to erode and clothing became interchangeable, Gold said.

But there’s a learning curve for men’s fashion. Some men have simply replaced the suit with a new workday uniform—khakis and a button-down shirt.

“Business casual will either be the death or rebirth of men’s fashion— if men can learn to do it right, it will open up a huge market for separates and ’premium sportswear,’” Gold said. “If not, slouchy khakis with tucked-in dress shirts will reign supreme.”

Where to shop

For many men, the challenge has been as much where to shop as what to wear.

When Los Angeles retailer Lisa Kline opened her second Robertson Boulevard boutique, Lisa Kline Men, five years ago, there were few contemporary retail stores catering exclusively to men and fewer resources to stock in those stores.

“There is a greater demand now than since I started my men’s store due to the fact that there are more great men’s stores across the country that are looking for cool goods,” said Kline. “There is an overabundance of great women’s stores and men like to dress great too, but without the help of new emerging designers or experienced designers creating contemporary stuff it is hard for the customer and the buyer.”

One of the labels Kline carries is Los Angeles- based Eisbar, a collection of contemporary denim-driven menswear that ranges in wholesale price from $14.50 for a T-shirt to $90 for an army jacket. Bobby Benveniste, owner and designer of the line, said that although he has seen the contemporary menswear business grow in the last season, he still sees plenty of room for growth.

“There are some great men’s stores across the country, but still you walk into Barneys and there are three floors of women’s and one and a half for guys,” he said.

Trade show scene

As the market opens up, small trade shows have launched to cover the category. Some shows carry both men’s and women’s apparel, including To Be Confirmed (TBC), held in London and New York, Pool, held in Las Vegas, and Agenda, held in San Diego and Los Angeles.

Others are targeting the men’s market specifically. The Project global trade show, organized by New York Atrium boutique owner Sam Ben- Avraham, just concluded its second show in New York. And, on the West Coast, the Westcoast Exclusive is adding younger, fashion-driven labels to its mix of upscale men’s lines at its trade shows in Los Angeles and Las Vegas.

“There’s a huge demand for contemporary menswear and there are a lot more retailers getting into the game,” said Project’s Ben-Avraham. “If the consumer sees the category in more stores he’ll get into it and that will create more demand. In a few years it will become one of the strongest categories in retail.”

The price/quality equation

Contemporary menswear—like contemporary women’s apparel—comes in at a new price point—higher than most street, skate and urban brands, but lower than designer and European labels. Consequently, there’s some price adjustment required of the men transitioning up to contemporary apparel from lower priced lines, according to some retailers.

Retailer Greg Armas recently opened his Scout boutique on Third Street in Los Angeles with a mix of vintage and new merchandise for men and women.

Many of the new lines Scout carries are limited edition, Armas said, adding, “Men respond very well to that—I don’t know if it’s the whole collector thing.”

As an example, Armas points to a screen-printed T-shirt from Los Angeles–- based label Astronaut.

“When I point out the different processes, then they are like, ’I’ll take three,’” he said.

Part of the boutique’s success may be due to its location, near other contemporary and designer women’s boutiques such as Aero & Co., Erica Tanov and Trina Turk.

“On Third Street I get a real quality shopper,” said Armas. “People come down here with shopping intentions. They already expect that a T-shirt is $40. They know if they are going to get something that is not mainstream, it’s going to cost.”

Plus, as Eisbar’s Benveniste points out: “When men’s jeans are coming in at $110 to $180, people are not going to bat an eye when spending $40, $50, $60 or $80 for a T-shirt.”

Exclusive designs

Designer Lane Reed incorporated the idea of exclusivity into the design of the clothing in his recently launched Cecil & Reed label.

The Long Beach, Calif.–based line includes styles with a series number embroidered right on the garment. A set number of a certain pant style will be produced and each piece will have the series number embroidered on a side seam. For example, the samples are labeled 0/250 and the first pair of pants shipped would be labeled 1/250.

“It gives us that extra little edge,” said Reed, who just started shipping his line to boutiques in New York, San Diego, Washington, D.C., and Japan.

“Guys are starting to understand that it’s okay to spend a bit of money to look good,” said Reed, who describes his customers as aged 20 to mid-40s, often in creative fields such as music or entertainment, with disposable income. His collection ranges in wholesale price from $59 to $120.

“Retailers are starting to latch on to that,” he said, comparing the men’s contemporary category to the early stages of the women’s contemporary category.

“Just like women’s a few years ago, $150 for a pair of jeans was over the top, but now it’s [not unusual],” he said.

Menswear trends tend to move more slowly and stick around longer than trends in the women’s segment of the business.

Designer Ryan Roberts describes the menswear business as “an evolution.”

“Every season I feel like I’m bringing newness, but what I like about menswear is you have time to explore an idea,” said the Toronto transplant who is now in his third full season designing his Ryan Roberts men’s line in Los Angeles.

The collection of semitailored separates in traditional men’s fabrics such as jersey knits and boiled wool sells in men’s boutiques in New York, San Francisco and Los Angeles. Wholesale prices start at about $40 for some of the knits, but Roberts said the average wholesale price in his line is $150.

“The retail accounts I have the most success with are the ones that are open to taking in any product knowledge I can give them,” said Roberts, who added that men are more receptive and less price-resistant if they understand the value of the fabric, construction and design.

“I always try to be the least expensive resource in the most expensive store,” Roberts said, adding that that strategy allows his merchandise to hang next to high-end designers like Yohji Yamamoto.

And, as men become more accustomed to shopping—and paying— for contemporary merchandise, they become less resistant to the price.

That’s particularly true if the designers continue to add newness and innovation to the product, said Eisbar’s Benveniste.

“If the customer is used to $30 and you offer $35 with all the bells and whistles, the customer is going to respond,” he said, adding, “You keep raising the bar—it may take a season or two for the consumer to catch up, but they will catch up.”