Wal-Mart Takes the Lead in Radio I.D. Tracking

Just as retailers and manufacturers were getting the hang of the bar-code environment of EDI (electronic data interchange), the latest development in tracking technology, radio-frequency identification (RFID), may be coming to stock rooms much sooner than anyone expected.

Bentonville, Ark.–based retail giant Wal-Mart Stores Inc. set the wheels in motion by asking its top 100 suppliers to become RFID-compliant by January 2005. Target stores, The Home Depot stores, and global, high-volume retailers Metro AG, Carrefour SA, Tesco PLC and Ahold USA Inc. have announced similar plans. On the apparel front, Prada has used RFID in one of its New York stores for the past 18 months.

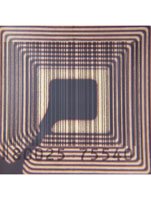

RFID technology uses radio waves and global positioning systems to track pallets, case packs and even individual garments by reading small chips. This eliminates the labor of scanning bar codes by hand or machine.

Manufacturers have developed several types of chips, which range from minuscule models to versions that are as large as Sensormatic tags. Some manufacturers, including Hitachi Ltd., have developed chips as small as 0.4 millimeter that are being used on currency in Europe and are being explored by several European retailers. When attached to garments or other individual items, RFID chips are embedded using fibrous tissues that adhere to a set of grooves.

The chips can store more information than bar codes and are also more efficient, according to technology executives. AMR Research Inc. said early implementations of RFID reduced supplychain costs by 3 to 5 percent and boosted revenues by 2 to 7 percent. The organization added that those figures are somewhat premature since the RFID market has been limited by the cost of the chips, which average from 25 to 40 cents each, and the cost of the scanners, which cost between $1,500 and $2,500 each.

The chief goal is to track inventory so retailers can replenish hot-selling items or promote slow sellers. The National Retail Security Survey put out by the University of Florida showed that close to 4 percent of annual domestic retail sales are lost because of out-of-stock inventory. In addition, the survey found that retailers lose close to $6 billion because of administrative errors.

“RFID is not a wholesale attempt to replace the UPC code,” said Marshall Gordon, apparel and footwear manager for Newtown Square, Penn.–based SAP America Inc., one of the first solution providers to integrate RFID. “I see it working in different ways. If you have someone coming into a store looking for a particular T-shirt in size Large, you don’t have to physically hunt it down or rely on an inventory database that could be wrong. RFID will tell you where it is in the store, whether it got mixed up in a wrong department or whatever. It will also allow you to scan containers and tell you what’s inside without assuming the ASN is correct. For some of these companies that have 100 containers sitting in their yards each day, that could be a tremendous help.”

SAP is one of the key players working with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and its Auto-ID Center to develop a global infrastructure for RFID.

“If you look at EDI, it took 12 years to get 1,000 vendors or suppliers on board,” Gordon said. “Then Wal-Mart, Kmart and Bullocks came along to support it and set a quasi-standard. Then you saw about 10,000 new vendors in three years.”

Tagged for growth

While the military has used the technology for years, manufacturers have only recently brought the cost of the chips down to make the technology feasible for mega-retailers such as Wal-Mart. The powerful, influential retailer could help spawn a big spike in RFID use over the next few years.

Oyster Bay, N.Y.–based research company Allied Business Intelligence Inc. (ABI) projects RFID sales will rise from about $1 billion to $3.1 billion within five years.

“Item-level tracking [tagging each garment] in the supply chain is no more than three to four years from widespread implementation,” said Erik Michielsen, ABI senior consulting analyst.

Some European retailers will launch itemlevel tracking by the end of the year. Kaufhof in Germany said it has begun an RFID pilot program that will track garments from women’s clothing supplier Gerry Weber International AG through the supply chain to two of its stores. The pilot program is part of the “Future Stores” initiative from Metro, Kaufhof’s parent company.

For now, Wal-Mart is requiring only cases and pallets to be tagged at the manufacturer level.

Though Wal-Mart is already using this new technology, many think it will be a long time before RFID is widespread in the apparel industry.

“The major manufacturers are not sophisticated enough right now,” said Henry Cherner of Santa Ana, Calif.–based Apparel Information Management Systems. “It’s tough enough for them to handle what they’re doing right now [with EDI and other technologies]. Then you have to deal with the regulation.”

Diane Magidson, product strategy leader for Waukesha, Wis.–based logistics company RedPrairie Corp., agreed.

“It probably will be like EDI, which took forever to be adopted—but then, RFID isn’t that new,” she said.

RedPrairie last week released its RFID Accelerator, a software application that collects and verifies RFID tag information, retrieves related inventory data and passes this combined information to the retailers in advanced shipping notices. It will help companies comply with the mandates being set by Wal-Mart, Target and others, Magidson said.

Companies such as Morgan Hill, Calif.–based Alien Technologies are supplying the hardware with a range of chips that feature short- and long-range readability, while companies such as Richardson, Texas–based Globe Ranger Corp. are supplying middleware products that act as interfaces between the chips and the readers.

Security and privacy issues are also hindering the implementation of RFID. Wal-Mart had planned to install RFID devices inside of shelves at its Brockton, Mass., store to track sales of Gillette razors, but the plan drew protests from several privacy groups that said the retailer should not track customers’ moves. Wal-Mart did not follow through with the plan and instead implemented RFID chips at the pallet and case levels, said a company spokesperson.

Benetton postponed an RFID initiative for its Sisley brand because consumers feared the retailer would act as “Big Brother” and track customers rather than merchandise.

“This is going to be a key piece of the puzzle,” Magidson said. “Retailers are going to have to figure out if they want to turn off the switch after the register.”

At its New York store, Prada removes the tags before items leave the shop.

Some companies, however, feel RFID can play a big role in nabbing shoplifters by tracking stolen merchandise to thieves. Retail sources see other long-term benefits, such as shopping carts equipped with RFID readers that can promote certain tagged items. And some companies are also gearing up RFID for the Internet by developing products with RFID-enabled URLs that will allow consumers to track their purchases over private Web sites.

Gordon of SAP America said companies such as Prada, S.p.A. are using RFID to help customers with their purchases.

“It can track what colors someone brings with them into their dressing rooms and give the sales associates ideas for add-on items,” he said.